Right View in the Weight Room: Lessons from Buddhism for Strength & Conditioning Coaches

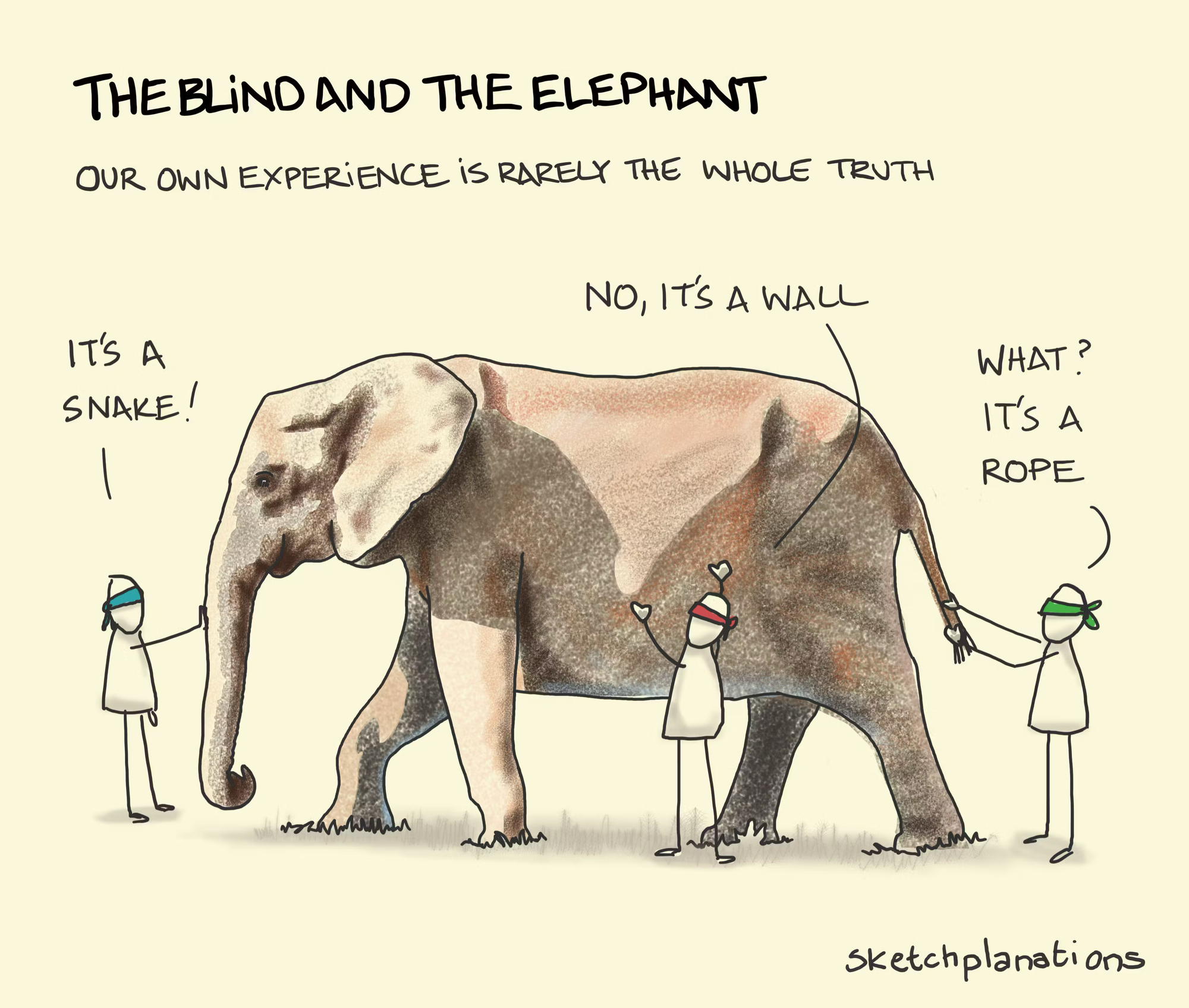

As strength coaches, we often see only part of the “elephant.” Buddhism’s teaching on Right View reminds us to balance objective, subjective, and intersubjective "truths"; helping us lead with humility, curiosity, and wisdom.

Strength and conditioning coaches love to argue. Amiright? We argue about Olympic lifts versus trap bar jumps. We argue about depth on squats. We argue about velocity-based training, RPE, GPS, and whether an athlete should “just go heavy” or stick to 1RM percentages. I’ve sat in meetings that turned into debates, debates that turned into battles, and battles that turned into bruised egos.

Why “Right View” Matters in Coaching

It took me years to realize most of these clashes weren’t about who had better data. They were about perspective. About what we saw, what we valued, and what we confused for “truth.”

This is where Buddhism’s idea of Right View comes in. Right View doesn’t mean having the “correct opinion” or the “best training philosophy.” It means learning to see clearly. To understand what you’re actually looking at, and what you’re not.

In coaching, Right View isn’t about winning debates. It’s about clarity. It’s about knowing whether you’re dealing with an objective truth (225 pounds is 225 pounds), a subjective truth (225 feels heavy to a freshman but light to a senior), or an intersubjective truth (225 is the “respectable bench press” in our culture).

When coaches argue, it’s usually because they’re mixing up which truth they’re talking about. I’ve seen coaching friendships strained, staff rooms divided, and programs derailed—not because anyone was wrong, but because they were 'all right' in different ways.

That’s why learning to see truth clearly is one of the most underrated skills a strength coach can develop. It doesn’t just make you a better coach. It makes you a better teammate to the sport coaches, a better leader to your staff, and a better servant to the athletes you’re entrusted with.

This blog article is about that. It’s about how to apply “Right View” to the weight room, the playing surface, and the conversations we have every day. It’s about a parable with six blind men and an elephant. It’s about learning to separate objective, subjective, and intersubjective truths. And most of all, it’s about how years on the coaching floor teach you that coaching wisdom comes not from clinging to certainty, but from practicing clarity.

Three Kinds of Truth in the Weight Room

When I first started coaching, I thought strength and conditioning was a science. If you just read the right journals, got the right certifications, and memorized the right progressions, you’d know the truth. Ooof.

But the more I coached, the more I realized: there isn’t just one truth. There are at least three, and they play by different rules.

1. Objective Truth

Objective truths are measurable, universal, and independent of opinion. If you load a barbell with two plates, it weighs 225 pounds, no matter how you feel about it. If an athlete runs a 4.62 in the forty, that’s their time. If a force plate shows 4,500 newtons of peak force, that’s what the plate recorded.

These truths are the backbone of sport science. They’re testable, repeatable, and not up for debate.

I remember testing vertical jump with a basketball team. One coach wanted to use the Vertec, another wanted to use the force plates. The athletes didn’t care. The force plate was giving us force-time curves, eccentric rates of force development, and peak power outputs. The Vertec gave us a number of tabs touched. Both sets of data were true. But only one was objective in the scientific sense.

Objective truths anchor us. But they don’t tell the whole story.

2. Subjective Truth

Subjective truths are personal. They’re how something feels, looks, or lands for an individual. Two athletes can run the same conditioning test, hit the same times, and one feels fine while the other feels wrecked. Both experiences are true.

We often dismiss subjective truth in strength and conditioning because it feels “soft.” But ignoring it is a mistake. An athlete’s perception of effort, fatigue, and readiness has real consequences. Their buy-in, motivation, and willingness to train often hinge on subjective truths.

We ran a brutal conditioning session one August. Objectively, every athlete finished within their time standard. Subjectively, one athlete walked away saying, “That wasn’t too bad.” Another slumped against the wall, head in hands, convinced they were about to puke. Both were right. Both needed different follow-ups: one needed to be reined in, the other needed recovery.

Subjective truths remind us that athletes are not just data points.

They’re human beings.

3. Intersubjective Truth

This is the most misunderstood category; and the one that creates the most conflict. Intersubjective truths are 'shared meanings'. They only exist because a group agrees they do. Money, laws, traditions, cultural values, and yes, weight room dogma, are all intersubjective truths.

In strength and conditioning, these truths shape culture. We decide that squatting below parallel is “real” strength. We decide that a 225-pound bench press is the threshold of respect. We decide that showing up late is disrespectful. None of these are objective laws of the universe. They carry weight because we agree they do.

In one program, we decided that every athlete would squat to parallel or deeper. If you cut depth, it didn’t count. Objectively, partial squats still load the quadriceps and build strength at certain angles. Subjectively, some athletes felt safer squatting high. But intersubjectively, our staff had declared: this is our standard. That agreement gave it meaning, and consequences.

The Problem: Confusing the Three

The real danger comes when we conflate these truths. We treat intersubjective truths like they’re objective (“real athletes squat below parallel; it’s science”). We dismiss subjective truths as irrelevant (“she says her back hurts, but the numbers look fine”). Or we ignore objective truths because they clash with our philosophy (“I don’t care what the GPS says, this is how we condition”).

That’s when coaching breaks down.

The first step toward Right View is simply asking:

Which truth am I dealing with right now?

Because clarity begins with categories.

The Parable of the Six Blind Men and the Elephant

One of the oldest stories in Buddhist and Hindu tradition is the parable of the six blind men and the elephant. You’ve probably heard it in some form before, but it’s worth retelling carefully; because when I first started seeing this story through the lens of strength and conditioning, it changed how I approached every debate in the field.

The Story Retold

Six blind men are led to an elephant. None of them have ever encountered such a creature before, and each wants to understand what it is. Since they cannot see, they reach out and feel different parts of the animal.

- The first man touches the trunk. “An elephant is like a snake!” he declares.

- The second grabs a tusk. “No, it’s like a spear.”

- The third feels the ear. “You’re both wrong—it’s a fan.”

- The fourth lays his hand on the leg. “No, no—it’s a tree.”

- The fifth pats the side. “You fools, it’s a wall.”

- The sixth pulls the tail. “Clearly, it’s a rope.”

They argue. Each insists his experience is the true one. None can see the whole animal, so each confuses a partial truth for the whole truth.

The moral is obvious: truth is vast, and our grasp of it is often partial. Conflict arises not because we are wrong, but because we mistake our limited perspective for the complete picture.

Why This Story Belongs in the Weight Room

Now, think about the debates we have in strength and conditioning:

- One coach swears Olympic lifts are the gold standard for power development.

- Another argues for plyometrics and medicine ball throws instead.

- A third insists velocity-based training is the future.

- A fourth dismisses all of it, saying, “Just get the kids strong.”

Sound familiar? Each coach is holding on to a “part of the elephant.” Olympic lifts do build explosiveness. Plyometrics do train rapid force production. Velocity-based training does bring precision to load prescription. Raw strength does underpin athleticism.

The problem isn’t that anyone is wrong. The problem is when we elevate our intersubjective truth (our coaching philosophy, shaped by our environment and mentors) to the level of objective truth (a universal law).

That’s how camps, cliques, and turf wars form in our field. Just like the blind men, we end up arguing over partial truths instead of working toward a fuller understanding.

The Blind Men as Archetypes of Coaches

Let’s stretch the metaphor a little further. Each blind man can represent a certain type of strength and conditioning coach.

The Trunk Coach (Snake)

This coach has latched onto movement as the essence of training. They emphasize fluidity, range of motion, and the art of athleticism. You’ll find them programming mobility flows, agility ladders, and change-of-direction drills above all else. To them, the “truth” is movement quality.

The Tusk Coach (Spear)

This coach is all about intensity and sharpness. They believe in aggressive outputs; max velocity, peak power, heavy loads. They design programs around testing limits. To them, the “truth” is sharp, focused stressors.

The Ear Coach (Fan)

This strength coach is fascinated by energy systems and recovery. Their programs revolve around conditioning, work-to-rest ratios, and flow of training. To them, the “truth” is about balancing exertion and recovery like the flapping of a fan.

The Leg Coach (Tree)

The traditionalist. The tree represents stability, rootedness, strength. This strength coach insists on foundational lifts—squat, bench, deadlift—as the true test of an athlete’s preparation. Their programs rarely stray far from the classics.

The Side Coach (Wall)

The system-builder. They see the big surface of things: culture, accountability, structure. Their focus is the program as a whole. Sets and reps matter less than buy-in, environment, and consistency. To them, the “truth” is the wall: what holds everything up.

The Tail Coach (Rope)

The minimalist. They believe less is more. Strip things down, use what you need, ignore the fluff. They see training as something you hold onto for leverage; simple, direct, utilitarian.

Individually, each coach sees something valuable. But if they refuse to acknowledge that they’re holding just part of the elephant, they end up in endless conflict.

The Elephant and the Weight Room

Here’s the real kicker: the elephant doesn’t care. It exists whether the blind men agree or not. The weight room is the same way. Athletes adapt based on stressors, not arguments. The body doesn’t care if your favorite philosophy wins the Twitter/X debate.

What matters is whether we, as strength and conditioning coaches, can step back and recognize that truth is often bigger than our corner of it.

When we fail to do this, we waste energy fighting over turf instead of serving athletes. When we succeed, we can integrate perspectives: using Olympic lifts and plyos, velocity-based monitoring and intuition, traditional strength work and sport-specific movement.

That’s what Right View invites us to do—not cling to the tail, tusk, or trunk as the “whole truth,” but hold our piece with humility, curiosity, and openness to others.

Problems When We Conflate Truths

Let’s tie this back to the earlier framework of objective, subjective, and intersubjective truths.

- The blind men mistake their subjective truths (what they feel under their hand) for objective truths (the entire elephant).

- When they argue, they’re asserting intersubjective truths (“my perspective is the perspective”), demanding agreement from others.

- The result is conflict and confusion, when in fact they’re all partially correct.

This is precisely what happens in strength and conditioning coaching debates. Ever attend the CSCCa National Conference? If you have, you've heard this battle of subjective, objective, and intersubjective truths play out.

One coach says, “Squats are the best exercise for athletic performance.” Another counters, “No, single-leg work is superior.” Objectively, both squats and single-leg work load the lower body and transfer force through the ground. Subjectively, one athlete may feel squats wreck their back while another feels empowered by them. Intersubjectively, certain programs or cultures elevate squats as the badge of “real training.”

If we confuse these categories, we get lost. If we can separate them, we gain clarity.

Applying the Parable to Coaching Conflict

I’ll never forget a heated discussion in a staff meeting years ago. We were planning offseason training for a particular sport team.

One coach argued passionately for more Olympic lifts. “We need to teach them how to move the bar explosively. That’s where the transfer happens.”

Another countered, “These athletes don’t have the time to master Olympic lifts. Plyos and med ball throws will give us more bang for our buck.”

I sat in silence for a while, then finally said: “You’re both right. The question isn’t which is better in general. The question is: which is better for this team, at this point in the season, with the time we have?”

The room went quiet. That moment shifted the tone. Suddenly, the conversation was about context, not absolutes. We stopped arguing about “the elephant” and started piecing together the parts we each saw.

That’s what the parable offers us: a reminder that the fight isn’t about whether the elephant is a snake, spear, fan, tree, wall, or rope. The fight should be about how to integrate partial truths into something closer to the whole.

The Takeaway for Strength and Conditioning

The parable of the blind men and the elephant isn’t just a story; it’s a mirror.

As coaches, we are all blind. None of us sees the whole elephant. Science gives us better instruments, but even force plates and GPS units only measure part of the picture. Experience broadens perspective, but even decades of coaching can’t eliminate our biases.

The key isn’t to find the “one true philosophy.” The key is to approach coaching with humility. To recognize that what we feel, what we measure, and what we agree on are all different types of truth. To stop mistaking our corner of the elephant for the entire beast.

Right View in coaching doesn’t mean never having opinions. It means holding those opinions lightly, open to challenge, ready to learn, and aware that what feels like ultimate truth may only be part of the story.

The Cost of Conflation in Coaching

Here’s where the friction really happens. Let’s play out some examples:

Mistaking subjective truth for objective truth:

A coach feels that heavy squats built their own athletic career. They universalize it: “Heavy squats are the best way to build power for everyone.” But athletes differ. For some, the risk-to-reward ratio doesn’t justify it.

Mistaking intersubjective truth for objective truth:

A department believes Olympic lifts are essential because “that’s what elite programs do.” But objectively, you can develop triple extension through many means; loaded jumps, trap bar pulls, sprints. The belief holds cultural weight, but it’s not a universal law.

Mistaking objective truth for subjective truth:

An athlete tells you they feel like their vertical jump hasn’t improved, even though the force plate shows a 4-inch increase. If you dismiss the data as “just their opinion,” you miss the chance to both affirm their subjective experience and ground them in objective progress.

Conflation leads to bad programming, fractured staff cultures, and endless online debates that go nowhere. It blinds us to nuance, the way the blind men missed the whole elephant.

Humility and Curiosity in Coaching Practice

The parable of the blind men and the elephant is not about who is right, but about how partial truths can be held with humility. When each man acknowledges that he only has a piece of the puzzle, collaboration becomes possible. In strength and conditioning, humility is the recognition that no single method, exercise, or philosophy captures the entirety of human performance.

Curiosity then becomes the natural partner to humility. Instead of defending your method, curiosity asks: What am I missing? What might another coach’s perspective reveal? What does the athlete in front of me need, not the athlete in my imagination?

Humility in the Weight Room

Humility shows up when a coach admits, “I don’t know everything about sprint mechanics” and seeks input from a track coach. Or when they test an athlete’s readiness and decide to adjust a pre-planned workout instead of stubbornly sticking to it.

Humility does not mean lack of confidence. It means recognizing that truth is often larger than our personal angle on the elephant.

Curiosity in Practice

Curiosity is when you watch an athlete move and instead of rushing to correct, you ask, Why are they moving that way? What does their nervous system know that I don’t?

It’s when you sit in on a peer’s session and instead of criticizing, you ask, What principle is guiding their choices? Could I learn something from this?

Humility keeps us grounded. Curiosity keeps us growing. Together, they transform how we apply Right View in coaching.

Applying Right View

Right View, in Buddhist thought, isn’t about possessing the correct opinion. It’s about seeing reality skillfully, acknowledging how perception is shaped by conditioning, culture, and personal experience.

In strength and conditioning, Right View is:

- Recognizing when you’re working from objective truths (force plate data, sprint times).

- Recognizing when you’re working from subjective truths (athlete feelings, coach intuitions).

- Recognizing when you’re working from intersubjective truths (industry trends, team culture).

The skillful coach can differentiate between these, move between them, and use each appropriately.

For example, imagine programming a taper before competition:

- Objective truth: The data shows the athlete’s workload has been high and their CNS is taxed.

- Subjective truth: The athlete reports feeling sluggish and unconfident.

- Intersubjective truth: The sport culture values hard practices before big games.

Right View helps you navigate this. Do you blindly follow the intersubjective pressure to “push hard,” or do you integrate subjective feedback with objective markers to make a better tapering decision?

It’s not about one truth overriding the others; it’s about holding them in relationship.

Wisdom is Built Through Reps

No coach is born with the ability to skillfully hold these truths. It comes with reps, not just in programming, but in navigating the human side of sport.

Every time you:

- Adjust a session because an athlete shows up exhausted,

- Defend your athlete’s needs in a meeting against cultural pressure,

- Integrate new sport science data into your methods,

…you’re building coaching wisdom.

Like strength, wisdom is trained over time. The first time you encounter conflict between objective and intersubjective truths, you may default to one side. The 100th time, you start to recognize patterns and respond with more nuance.

This is the essence of experience; moving from instinctual reaction to thoughtful response. Coaches who can “see the elephant” more fully aren’t smarter; they’ve simply put in the reps of making, reflecting on, and refining decisions.

The Broader Implications Beyond Coaching

These truths don’t just shape the weight room; they shape how we live.

- In politics, subjective truths (lived experiences) clash with intersubjective truths (party ideologies) and objective truths (data, laws). Most debates devolve because participants mistake one for the other.

- In relationships, conflict often arises when one partner universalizes a subjective truth: “I feel this way, so it must be the truth.”

- In society, we frequently mistake intersubjective truths (money, nationalism, cultural norms) as if they were objective.

Strength and conditioning is a microcosm of life. If we can learn to hold truths skillfully in sport, we can carry that wisdom outward into leadership, family, and community.

Seeing the Whole Elephant

The parable of the blind men doesn’t end with them seeing the whole elephant. But as coaches, we get that chance. By layering objective, subjective, and intersubjective truths, we can form a fuller picture.

Right View is not about being right. It’s about seeing clearly; with humility, curiosity, and compassion. It’s about knowing that what’s true for you may not be true for someone else, and that doesn’t make either of you wrong.

Strength and conditioning debates, much like life debates, lose their sting when we hold our truths lightly. When we recognize that we’re all touching the same elephant; just from different angles, we stop fighting and start learning from each other.

That’s the heart of coaching wisdom: not clinging to your piece of the elephant, but helping athletes and colleagues see the bigger picture together.